If you love to talk about the weather — or want to help collect information about it — a new smartphone app may be for you.

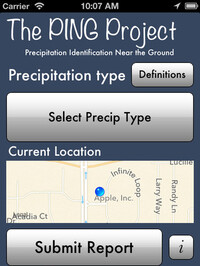

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Oklahoma are giving regular folks an opportunity to fiddle with weather reporting. Using crowdsourcing, the mobile Precipitation Identification Near the Ground app collects geographic, winter precipitation data from users. The mPING app also links to a map showing weather reports sent in by locals.

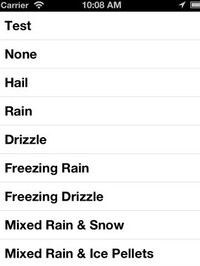

The data collected by the app will help weather officials program radar to determine exactly what's falling near you. For example, is it hail or mixed rain?

The free app is currently available for the iOS and Android operating systems.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Oklahoma's new mPING app helps forecasters capture a better description of falling precipitation.

Users anonymously update reports by selecting a variation of winter weather between "none" and "graupel/snow grains,"* their GPS location is noted, and information is sent in to NOAA. (It can also be done through NOAA's website, but an extra step of figuring out your longitude and latitude has to be completed.)

"The purpose of PING is to give us ground observations of precipitation types that are not well observed from automatic systems," Kim Elmore, a science researcher working on the project, told All Things Considered. He says the gathered information will be used to build algorithms for newly upgraded radars.

The data can also help officials and the public prepare for severe weather, he says.

The PING project captures data from locals on its app or website. Users are able to choose from different types of precipitation.

"If we can better marshal our resources for dealing with it, then it may not cost quite so much and people may not be in quite such jeopardy," Elmore says. Throwing salt, buying sand, fixing wires and removing fallen trees can be constant expenses, he adds.

mPING is just the latest weather app to use crowdsourcing. Others include Weddar, which asks users to add a colorful description of the weather; and Metwit, a hyperlocal app that lets you pin photos to your weather reporting.

The app had a "soft launch" in December, but it has already become popular.

Elmore estimates about 20,000 people have downloaded the app and nearly 60,000 reports have been submitted. The project itself has been around since 2006, using different methods like cold-calling to verify falling precipitation.

Much of its popularity may come from the high level of interest in weather and science, Elmore says. The "real hook" is the data readily available for people to view on their phones.

So this app may not break the ice for your weather forecasting career, but it may someday help your local weatherman have an accurate picture of what's going on outside your window.

* In case you're wondering, NOAA's National Severe Storms Laboratory says graupel (aka soft hail or snow pellets) are "soft small pellets of ice created when supercooled water droplets coat a snowflake."

NPR Digital News intern Brian De Los Santos contributed to this report.

9(MDE1MTIxMDg0MDE0MDQ3NTY3MzkzMzY1NA001))

Transcript

ROBERT SIEGEL, HOST:

From NPR News, this is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED. I'm Robert Siegel.

MELISSA BLOCK, HOST:

And I'm Melissa Block.

As New England continues to dig out from snow, it's comforting to know that there's now an app for winter weather.

DR. KIM ELMORE: The app is called mPING, for mobile ping, and ping stands for the Precipitation Identification Near the Ground project.

SIEGEL: That's meteorologist Kim Elmore. He's part of a team that created the app. He says after a few months of quiet testing, its roll out culminated last week. It uses crowd-sourcing to collect local conditions, asking users to record the actual weather they're experiencing. Results get sent to NOAA's National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Oklahoma.

Again, Dr. Elmore.

ELMORE: We want these ground observations because we want to build algorithms for the newly upgraded dual pole radars.

BLOCK: He says to test the accuracy of their new and advanced radars, they need lots of citizen scientists around the country to send in their weather observations of rain, snow and sleet.

ELMORE: It sounds like we should know that but it's not as easy as it would appear. And we have to have access to observations like this to be able to validate how well anything we build works; and to actually build those applications and those algorithms.

BLOCK: Now, while that's the primary purpose of this app, anyone can go online and see reports people have sent in. Elmore says that curiosity explains why tens of thousands of people reported in from New England during the weekend winter storm.

ELMORE: Everyone is at some level interested in weather. And I suspect that the real hook is that the data are available for anybody to look at.

SIEGEL: NOAA hopes these sightings of snow, sleet and rain will eventually benefit forecasters and, in turn, all of us.

ELMORE: Winter weather probably costs us more money than any other kind of weather event. And it's just this constant expense. And if we can better marshal our resources for dealing with it, then it may not cost quite so much and people may not be in quite such jeopardy.

SIEGEL: Dr. Kim Elmore, of the Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, he's one of the people who worked with NOAA and the University of Oklahoma to perfect mPING - a new smartphone app that lets users report winter weather conditions. The app is available for Apple devices and Android. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad