In 1776, the American colonies declared independence from Britain.

But it wasn't until 1796 that someone dared to tackle a question that would plague every generation of Americans to come: "What is American food?"

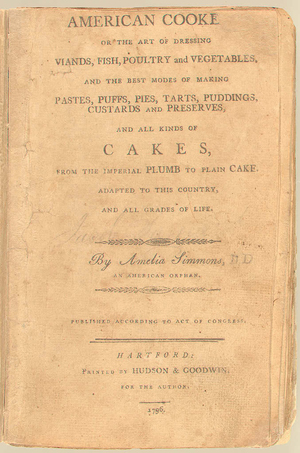

Cover of American Cookery by Amelia Simmons. First edition: Hartford, 1796. Printed by Hudson & Goodwin

American Cookery, the very first American cookbook, was written by Amelia Simmons (more on this mysterious woman later). In it, she promised local food and a kind of socioculinary equality. The title page stated that the recipes were "adapted to this country and all grades of life."

Up to that point, colonial housewives had access to cookbooks, but they were mostly reprints of popular British works, like Eliza Smith's The Complete Housewife. No homegrown cookbook included the innovations, local ingredients and emerging patois of the newly liberated colonies.

"So many firsts and milestones of American cooking appear in this small volume," says Jan Longone, who oversees the Janice Bluestein Longone Culinary Archive at the University of Michigan's libraries.

Take, for example, bacon smoked with the cobs of Native American corn or maize, and baking with a powder called pearlash — essentially, an "impure potassium carbonate obtained from wood ashes." It made the fluffy American muffin the answer to an airy French cream puff or a yeasty loaf of Italian bread.

But American Cookery's real contribution was the way it showed off indigenous foods, like "the makings for a traditional American Thanksgiving dinner," says Longone. You guessed it: turkey, cranberry sauce, squash and pumpkin pie.

Even in using more familiar ingredients, American Cookery sometimes reads like a guide to new American idioms: molasses rather than British treacle, and emptins [emptyings] instead of ale yeast. It includes an early sighting of "shortening" and the "Indian slapjack" that became the flapjack of today.

But for all this, the book was still deeply British. At a time when cookbook writers often plagiarized one another, it co-opted recipes popular in the motherland. The inclusion of dishes like "Shrewsbury Cake," "Marlborough Pudding," and "Royal Paste" showed there was still a place for tradition in this new American cookery.

But it also showcased the very American value of self-improvement as both civic duty and national pastime — and that we could change our lives if we could change what we eat. The author, Amelia Simmons, claimed to be an orphan of the war who longed to make women, she wrote, "useful members of society." She dedicated herself to "the improvement of the rising generation of Females in America" by teaching them to cook according to the book.

But this is where the book's promise to school the new republic in the ways of its national cuisine starts to look like an exercise in branding.

Andrew Smith, the editor of the Oxford Encyclopedia of Food and Drink in America, and others wonder if there ever was an Amelia Simmons. "There's no evidence that any person by the name of Amelia Simmons ever lived," he tells The Salt. "My personal suspicion is that it's a pseudonym for somebody else."

Smith also sees the "American" cooking of the book as largely a "terse, Spartan" cuisine specific to New England. "That's very different from Middle States, very different from New York City," he says, "very different from Southern cooking."

He points to 1863 as the defining moment for American food. Prior to that, "American cooking was regional cooking," not national. But the Civil War "destroyed Southern cooking," and as newly freed slaves migrated North, the nation's cuisine "only becomes American because many of the cooks from Southern plantations are African-American, and they end up in New York City cooking in restaurants." And those changes stick with us today.

And yet some American food has truly been lost forever. Take the long-lost Illinois prairie hens — just one of the quintessentially American foods that writer Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain, longed for while in Europe. Andrew Beahrs, author of Twain's Feast: Searching for America's Lost Foods in the Footsteps of Samuel Clemens, says that the hens were once "eaten coast to coast," and even served in New York's Delmonico's restaurant. In Clemens' youth, the hens numbered in the millions. "Now there are only 300 left in the state, and those have been brought in from Minnesota," says Beahrs.

What has persisted? Social media. The formal Americanization of food that started in American Cookery soon evolved into newspaper recipe contests, women's magazines, and eventually, radio and television to help Americans think they are what they eat.

Food manufacturers, like Campbell's, also played an important role in refining the sense of what it means to eat American. "Many of the recipes that were developed by food processors end up in American cookbooks," says Smith.

And today? Smith admits, "I don't know if there ever was a real American food, but there are foods that Americans consume that other people didn't."

Longone, who has devoted her life to American food in print, concedes, "there's no such thing as a perfect answer" about what American cooking is.

9(MDE1MTIxMDg0MDE0MDQ3NTY3MzkzMzY1NA001))

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad