In May, a kitchen fire at a low-rent apartment in Greensboro claimed the lives of five refugee children—siblings from the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

After months of investigation, officials determined that “unattended cooking” was the likely cause, but the tragedy led to dozens of tenants stepping forward to share their stories of what they described as landlord neglect at the Summit-Cone apartments.

The 42-unit complex is owned by Bill, Sophia and Basil Agapion, and managed by Arco Realty. In the second installment of our five-part series “Unsafe Haven,” WFDD's David Ford investigates Arco, and the Greensboro family that has run the company throughout its 60-year history.

“Long List Of Code Violations”

Every home in Greensboro—owner or tenant-occupied—must meet minimum housing standards: safe, sanitary, and fit for human habitation. But often even those basic thresholds are not being met.

At a routine home inspection, Mark Wayman with the city's Code Compliance Division is checking out a property in East Greensboro on a tree-lined narrow street, dotted with small rental homes in various states of disrepair. He points to work being done to secure windows of the home.

“For the safety of the neighborhood and also to protect what's there, we're going to go ahead and do that," says Wayman. "The owners had more than twelve days to take care of this and they have not.”

Wayman adds that the missing windows and an open crawl space are ideal entry points for rodents, children, and homeless adults. He scans the scene and ticks off a long list of code violations including a crumbling front porch foundation, gaping roofline holes, vandalized electrical panel, suspect roof, missing handrails—and those are just on the home's exterior.

“It would take five minor violations or one major violation to start a case,” says Wayman. “And I think we definitely have one here, just at a glance.”

Coincidentally, the day after this home inspection tour, Wayman called to say that the owner of the small rental we visited just happens to be Irene Agapion-Martinez, of Arco Realty.

She's also the property management representative for the Summit-Cone apartments, the site of the deadly fire where nearly 500 minimum housing standards code violations were discovered after the fire. The entire complex was condemned, the second time in less than five years.

“A Reputation For Cutting Corners”

Built in the early 60s near the busy intersection of Summit Avenue and Cone Boulevard, the apartments are not much to look at: nine brick, barracks-style, two-story buildings spread out across one long block along Summit. But back in 1963, just a year after construction, to young real estate lawyer Bill Agapion, it looked like a money-maker.

Roughly ten years earlier he formed AAA Realty—later Arco Realty—in a converted bank building on South Elm Street. Specializing in low-income housing for people with very few options, he catered to those with poor credit, recent evictions, and the underemployed, and at Summit-Cone, immigrants and refugees.

Arco's stated mission: provide quality, affordable rentals. But by the 1970s the Agapions' reputation for cutting corners was already well established.

When a landlord's property fails to meet minimum standards, the buildings can be condemned, resulting in fines, civil penalties, reinspection fees, orders by the city to repair, and in extreme cases, demolition. Bill Agapion has a well-documented history of delaying fine payments, postponing necessary repairs, and bringing his apartments up to minimum code just in time to avoid demolition, says journalist Eric Ginsburg.

“This is a landlord who is not doing anything proactive to make sure people are living in safe conditions,” says Ginsburg.

Three years ago, he reported for Triad City Beat that the Agapion family, through their hundreds of Greensboro properties, had accumulated nearly $350,000 in outstanding fines.

“This is someone who does the minimal amount that they have to, and they only make those minimal changes when they're caught by the city,” says Ginsburg. “And that has a huge cost for the rest of us.”

Ginsburg says neighborhoods and the city pay for blighted apartments: depressing property values, the ability to attract new employers, and the jobs that come with them.

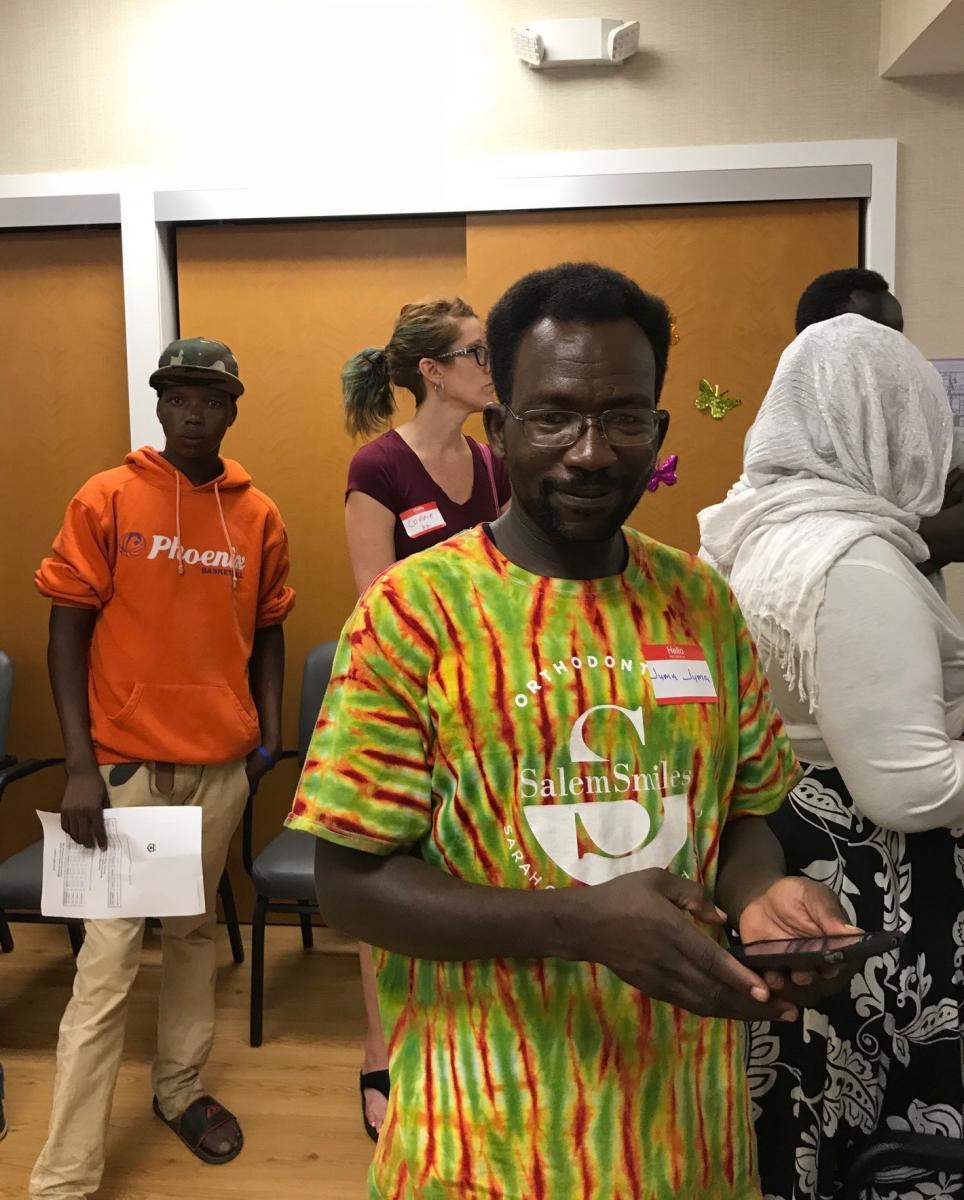

But for Sudanese refugee, and former Summit-Cone tenant Juma Juma, inaction on the part of his property manager, Arco Realty, led to months of frustration and anger.

“The landlord was not so courageous to come and see what's inside to evaluate either [if] the light is working or the fire detectors or the water either it is leaking or not leaking,” says Juma.

WFDD reached out to the Agapions on multiple occasions to request interviews for this story. Those requests were denied, but finally a written statement was provided through their attorney's office.

"Many criticisms we currently face are not factual or do not account for complicating factors. Regardless, we will continue to work to provide our residents with safe, affordable housing, to improve and maintain the properties we manage, and to serve our community as good corporate citizens."

It goes on to reiterate that the Greensboro Fire Department concluded that the fire was a result of unattended cooking by tenants.

For city officials and inspectors who have dealt with the Agapions over the years, accruing multiple violations and delaying repairs until the last possible moment is a familiar pattern, but not an illegal one.

Former Greensboro Chief Code Enforcement Officer Beth Benton describes her office's relationship with Irene Agapion-Martinez as cooperative.

“From my perspective, if you own hundreds and hundreds of properties, you're going to have violations,” says Benton. “That just kind of comes with the territory.”

Benton blames some of the backlog in tenant complaints in apartments primarily populated with refugees on language barriers, education, and the process itself.

“They don't realize that they have another option, that they can call us if the landlord is not being responsive,” she says. “The other thing [is] a lot of immigrants and refugees settling here often see code officers—we are a form of government, we are a form of police. So, we are not welcome. It creates fear from where they're from as political refugees."

“Unwanted Headlines”

And the code violations continue to accumulate. Members of the Agapion family are currently being sued by the widow of a plumber electrocuted while working in the crawl space of a rental property managed by Arco Realty. The suit alleges that the electrical system had bare wires and was dangerously below code. Bill, Sophia and Basil Agapion responded in nearly identical filings denying those claims.

Decade after decade, the Agapions have made unwanted newspaper headlines:

2006: Judge signs city order to demolish several Arco homes on Guerrant Street.

1992: Dozens of refugees from Vietnam settle at Summit-Cone apartments, which had been condemned and vacant.

1987: Survey shows 200 of the city's 250 boarded-up houses are owned by Agapions.

And the paper trail dates as far back as 1970, when hundreds of AAA Realty tenants staged a 3-month rent strike. Some marched past the Agapion's South Elm office holding signs that read: “When does this city plan to do something?”

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad