"Get in line" is what William Anderson, former chairman of the Moapa Band of Paiutes, says of the current take-back-federal-lands movement.

Ever since a tense, armed standoff near Cliven Bundy's Nevada ranch in 2014, a vast and sensitive piece of federal public land adjacent to the Grand Canyon has gone unmanaged and unpatrolled.

It's safe to travel into the area called Gold Butte so long as you're not in a federal vehicle, according to Jaina Moan of Friends of Gold Butte, which wants to see the area federally protected.

The last time there was any known federal presence was last summer, when scientists under contract with the Bureau of Land Management were camped here, gathering field research.

"Unfortunately that also was canceled after shots were fired at one of the contract crews," Moan says.

Gold Butte, roughly the size of Los Angeles County, is basically lawless right now. Trash is dumped here and there. Some of the BLM's route markers are torn down. Illegal off-road tracks from ATVs lead into the desert. Some pioneer gravesites were even dug up, bones scattered everywhere.

Gold Butte's red rock cliffs and slot canyons are home to many ancient petroglyphs. Some, like this one, have been shot at and damaged since federal land managers left the area due to safety concerns.

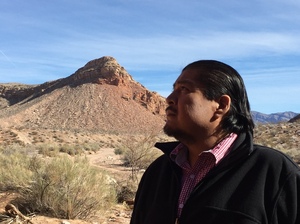

If no one is patrolling it, who's going to deter vandals? That's a question Moan and William Anderson, the former chairman of the local Moapa Band of Paiutes, who consider this desert sacred, are asking more and more as the dispute between Bundy and the government drags on.

The occupation of a federal wildlife refuge in Oregon has renewed attention to the federal government's case against Bundy in Nevada. The government's inaction against him is often cited as emboldening his sons to storm the refuge this month.

In southern Nevada, meanwhile, scores of the family's cattle continue to graze illegally in and around Gold Butte.

Cattle have been grazing in the vast Gold Butte area since an armed standoff between the government and self-styled militia in 2014.

William Anderson watches with frustration as a mangy-looking group of them crosses a four-wheel-drive road in the heart of Gold Butte. He considers the cattle a threat to desert grasses and plants that his people have gathered and used out here for generations.

"[The cattle are] out here just roaming the area and they are stepping on areas that are culturally sensitive to our people," he says.

No one knows for sure how many cows are roaming here since federal agencies pulled out of the area shortly after the standoff.

The Nevada state director of the BLM, John Ruhs, defends the agency's decision to keep field staff away. He says there are still threats and intimidation tactics directed toward his employees there.

"When it comes to having employees on the ground doing things like monitoring or restoration work, it's just not getting done because of the safety concerns we have for our employees," Ruhs told NPR.

Ruhs would not discuss the government's case against Bundy, and neither would the Department of Justice. But Ruhs did say that he now requires his staff doing fieldwork elsewhere in Nevada to go out in teams, never alone. It's a frustrating climate, he says. The BLM's mission is to manage public lands for all sorts of uses by everyone, not just cattle ranchers.

"We don't do anything on our own as personal individuals," Ruhs says. "We do things that are mandated from Congress, and we follow the laws that are given to us, and we try to enforce them appropriately."

Nevada has a long and troubled history with these sorts of domestic insurgencies. In the 1990s, bombs were placed on U.S. Forest Service property and the BLM's state headquarters in Reno. The case against Bundy and his unpaid grazing fees goes back some 20 years, too.

Land managers in the late 1990s also planned to round up some of his cows that crossed into the Lake Mead National Recreation Area. Alan O'Neill, who was superintendent there at the time and is now retired, recalls that at the last minute, the federal prosecutor stopped it, worrying of a Waco-type situation.

"When people break the law and there's no penalty, it just emboldens them to continue to do that," O'Neill says.

Bundy and his supporters have told NPR in recent interviews that their fight is about a lot more than cows. Like a lot of the mountain west, rural Nevada's economy has struggled and Bundy is one of the last ranchers in this corner of the state. Many were forced out or bought out over the years as Las Vegas expanded and federal environmental laws got tougher.

Still, the current movement to take back federal land that the Bundys and others have led is infuriating to people like William Anderson of the local tribe.

"They can get in line — we're saying the same thing about our people, too," Anderson says.

Back in Gold Butte, Anderson points out a petroglyph panel on a red rock slope. Two of the ancient drawings have recent bullet holes.

"It's really hard to even believe that somebody would come in and try to destroy it, or remove it," he says. "It's something that's been here forever."

Anderson says Gold Butte should be protected and managed by the local tribes.

9(MDE1MTIxMDg0MDE0MDQ3NTY3MzkzMzY1NA001))

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad