This country has a big problem: its children are not good readers.

Five years after the pandemic first closed the nation's schools, national test scores show students backsliding in reading all over the United States.

There was one exception: Louisiana. In 2019, Louisiana's fourth graders ranked 50th in the country for reading. Now, they've risen to 16th.

According to an even more granular analysis, Louisiana is the only state that has not only made a "full recovery" from the pandemic in both math and reading, but has improved upon its reading scores since 2019. Nearby Alabama has done the same in math. Those results come from the Education Recovery Scorecard, a joint venture by researchers at Harvard and Stanford.

So what's in Louisiana's secret sauce?

We went to Natchitoches Parish School District to find out: It's one of Louisiana's poorest school districts, up against some of the biggest hurdles to student achievement, yet it has managed to quickly grow its reading scores.

A remarkable turnaround

The rural town of Natchitoches (pronounced NAK-UH-TUSH) boasts in pamphlets and placards about its rich history: it is the oldest permanent settlement in what became the Louisiana Purchase. Its main thoroughfare, laid with cobblestones along the Cane River, is full of old-timey charm.

But for decades, the parish struggled with a persistent problem with its schools: It was one of the worst-performing districts in a state that long ranked at the bottom of the country.

In the last five years, the Natchitoches Parish School District has made a remarkable turnaround.

About 91% of its students are considered economically disadvantaged, but Superintendent Grant Eloi says he refused to let that mean lowering expectations for students.

"If you don't expose them to the highest level of rigor, then what chance do they have at making it out of the cycle of poverty?" To help understand how this district and the state improved literacy so rapidly, Eloi thinks back to when he first came here, almost exactly five years ago.

"I was named in the position the day the world shut down," he says, referring to the start of the pandemic. And with it, schools closed their doors around the country.

Eloi was an experienced educator, but he says he didn't realize just how "acute" the problems in his new district were: "We were worse off than every parish that touched us."

In his early days as superintendent, Eloi noticed there was little cohesion. Each of the district's 14 schools was doing its own thing. "It was like everyone survived the day. Buses came on time, it was like, 'we're good.' And that wasn't improving student achievement at all."

He and his team had big plans, and the pandemic wasn't going to slow them down: "Every school is going to have the same expectations, and we are adamant about that."

"We needed to make differences in a hurry"

To train teachers and help set expectations, Eloi brought on Kathy Noel, who had helped raise student achievement in another school district.

For Noel, who now serves as the school improvement specialist in Natchitoches, it was personal: She was born and raised in this town. She went to school in this district, as did her children and now, grandchildren.

A big part of the problem, says Noel, was that students simply did not know how to read. "We needed to make some differences in a hurry, not only in Louisiana, but also back here in my hometown."

With COVID relief funds and a grant from the federal government, Noel helped create a clear system for tracking student achievement goals, training a cadre of experienced educators called "master teachers," and adopting state-approved instructional materials.

Some of these reforms came as a result of steps the state has taken in recent years, and in other cases, Natchitoches was ahead of the curve.

"The state and us were simpatico. Sometimes they thought about it first, sometimes we thought about first," Eloi says. "But I really felt like we were in parallel lines of each other."

Teaching with new materials, based on the latest research

For more than a decade, Louisiana's department of education has reviewed instructional materials for quality to ensure what's being taught in classrooms lines up with the latest education research. Its focus has largely been on pushing literacy reforms to improve reading.

"What we've been able to do over the last five years is really train our educators and empower educators to utilize those high-quality instructional materials," says Jenna Chiasson, deputy superintendent at the state's Office of Teaching and Learning.

Louisiana has trained thousands of teachers to use state approved materials, including mentor teachers who specialize in literacy.

Louisiana is a local control state, and each district is, in some ways, free to choose how it teaches its students. But the state incentivizes schools to use those high quality materials: For lower-performing schools to get certain funds from the state, they must use state-approved curricula.

For reading, those materials include a strong focus on evidence-based research instruction, or the "science of reading."

In 2021, Louisiana began requiring K-3 teachers and administrators to receive training in the science of reading. Other states have similar laws, but experts say Louisiana was ahead of the curve.

In Natchitoches, 100% of teachers had completed the required training by the state's deadline in 2023, while 70% of teachers across Louisiana had done so, according to state data.

How teaching kids to read "has changed tremendously"

Before the state's reading training, Kathy Noel remembers observing teachers who were using what's known as "whole group instruction"—teaching the entire class one lesson, together.

"It was, 'I'm going to read to you, you tell me what I read'," she explains. "We were just pretty much hoping they would read and, as you know, hope is not a strategy."

That approach can mask big differences among individual students: In a chorus of young voices, lower-performing children were simply echoes of better readers.

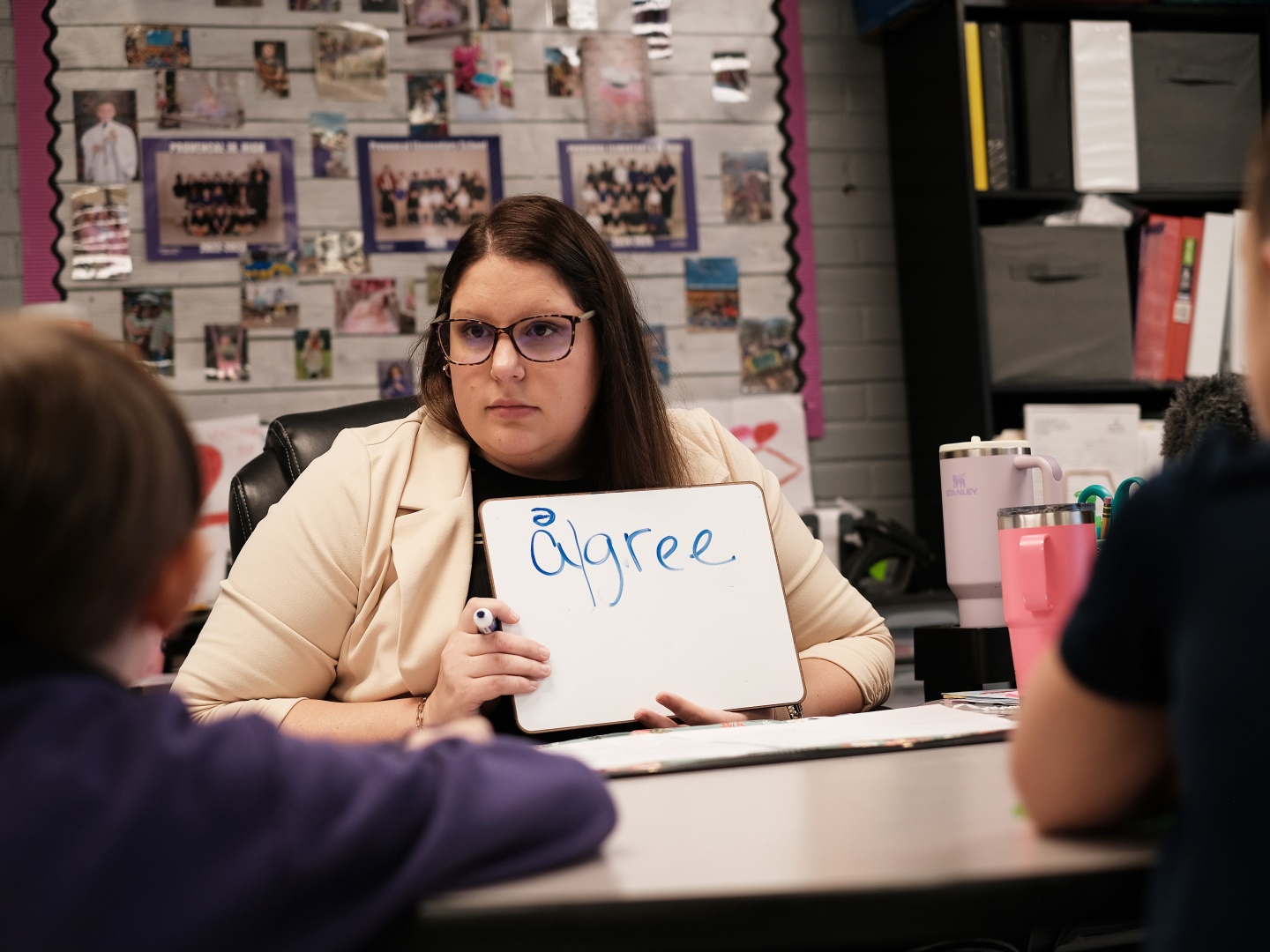

Cady Caskey has taught at Provencal Elementary School in Natchitoches for 11 years, and says the science of reading training "changed tremendously" her instruction.

"I have really transformed into more small-group instruction so that I'm able to tailor it per each individual child's needs."

Now, when you visit Caskey's vibrant second grade classroom, she begins her reading lesson with the children sitting on a carpet, engaging together for about 15 minutes.

Then, they break off and rotate through small groups, based on their reading level.

Some students work directly with Caskey at a kidney table, practicing phonics skills, like sounding out and decoding words. Others do group activities, or read independently.

Compared with five years ago, Caskey says, her students are "more engaged now because they are doing things that they can do … now it's on their level. So if they don't get it, I'm right there and can support them."

Across the district, students who are struggling with reading get additional interventions, in even smaller groups, every morning for 45 minutes. Higher-level readers take enrichment classes like coding, art or gardening.

Now, this kind of structure exists at every school in the district.

Ongoing support for teachers, and lots of data

All 14 schools in the Natchitoches district have at least one master teacher; most have two. These veteran educators observe classrooms, sometimes stepping into a lesson to co-teach, or even model instruction for a teacher. Master teachers also analyze student data to determine what's working and what isn't.

Each week, they lead "cluster meetings" for classroom teachers. In a recent one, master teacher Chrissie York led a session on "continuous blending" of words—a phonics strategy that teaches students to stretch out the sounds in a word to ultimately decode it.

Earlier this year, first and second grade teachers at Provencal noticed their students were successfully identifying the individual sounds in a word: "KUH-AH-T," for example. But when it actually came to forming the entire word and recognizing it as "cat," they struggled.

So, teachers field-tested the continuous blending strategy to see if it would help. "And we have found that it made, the numbers show, a huge difference," says Caskey.

She thinks back to how much she struggled in her early years of teaching, and the difference a master teacher, and regular data, could have made back then.

"Now, if I have a question or I'm struggling with figuring something out, I have somebody who I can bounce ideas off of. I have somebody to come in and support me."

A strong state focus on literacy

The layers of support for educators work up to the state: the district has reading specialists who work with each school, and the state has a dedicated literacy team that roves through different, higher-need districts across the state.

For more than two decades, Louisiana has had a strong system for holding its schools accountable and that system has evolved over the years. A new, more rigorous set of standards takes effect in the 2025-26 school year, and will now incorporate K-2 reading skills.

"The Louisiana accountability system is stronger than many other state systems," says Susan Neuman, a literacy expert and former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Elementary and Secondary Education under George W. Bush. Struggling schools there, she says,"are going to be scrutinized, examined in much greater depth."

And starting this year, Louisiana third graders who aren't reading at grade level will be held back and receive extra support. While retention policies have been cause for debate, research has shown the approach helped improve and sustain reading gains in Mississippi, especially for Black and Hispanic students.

"It feels good to not be at the bottom"

Kathy Noel is relieved her state and district are finally becoming models for the rest of the country.

"Down here in the South, we don't want to be last," she says. "It feels good to not be at the bottom and to not be looked down on."

While Natchitoches' reading growth has been impressive, educators recognize their students' scores are just slightly above the 2024 national average. So, they're striving for more. But maintaining good student outcomes requires money.

COVID relief funds from the federal government ran out last year, meaning Louisiana, along with the rest of the country, will have less to invest in student achievement.

Jenna Chiassion at the state education department says Louisiana used some of those funds to create a free, science of reading training that will be available for years to come. Federal grants will help keep literacy reforms in place, for now.

Natchitoches' school district also earned a $14.26 million federal grant in 2023, which helped pay for many of the programs that have led to its rapid growth. That money runs out after three years, and with federal spending cuts, including in the U.S. Department of Education, some at the district worry such programs could be affected.

"What we've done costs a lot of money," says Eloi, the superintendent. But, he adds, the federal grant allows for a sustainability plan, which his team is working on:

"We see the value of our master teachers, and I don't care what it takes, we're going to keep those systems in place."

Kathy Noel says making sure children know how to read remains a guiding light.

"There are consequences for graduating on time. There are consequences for having a higher paying job in the future," she says. "There are consequences for being a citizen. So if you think about the broader aspect of reading, why wouldn't we make it the foundation for student learning?"

Reporting contributed by: Aubri Juhasz

Producing contributed by: Lauren Migaki

Digital story edited by: Steve Drummond

Visual design and development by: Mhari Shaw

300x250 Ad

300x250 Ad